Initiated by Globe Art Point in collaboration with the municipalities of Sipoo and Porvoo, GAP LAB Svenskfinland brought together five artists in the spring of 2022 to develop a new project engaging inhabitants of the two municipalities. Specifically, the idea was for the artists to meet with locals who might not enjoy easy access to cultural services, which in Sipoo and Porvoo typically operate only in a few centralized locations.

Together with Beniamino Borghi, Therese Kühl, Riband Kurd and Jordy Valderrama, I was invited to join the interdisciplinary team of artists tasked with creating artistic encounters with Sipoo and Porvoo locals. The experiences found within our team were exciting, spanning different forms of expression such as mime and site-specific installations, painting, photography and contemporary dance. Our process resulted in a communal art project that we chose to call The Forgotten Keys, exploring social imaginations through the symbolism of the key as an instrument of access. Here I will try to tie together reflections on the project with thoughts on the key as a tool of access and passage, actual and potential.

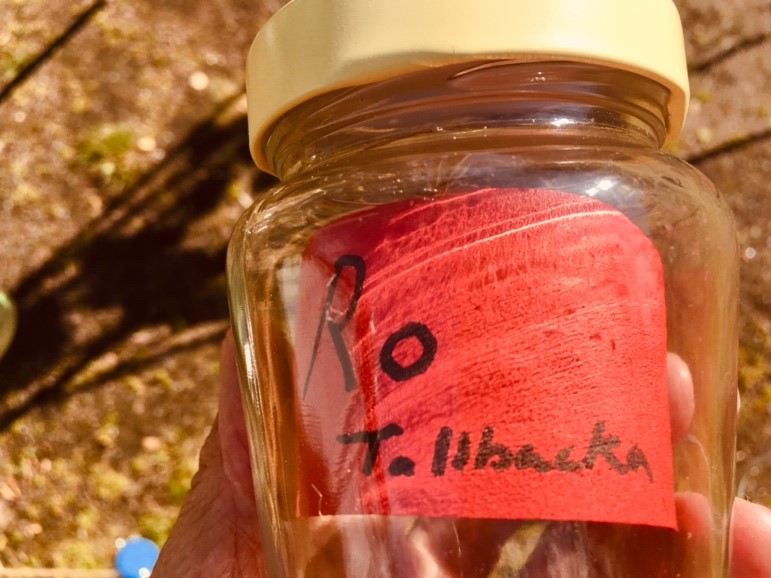

During the first half of June, we held ten workshops across Sipoo and Porvoo. We met locals and visitors in parks and parking lots, public swimming pools and summer markets, while also arranging workshops with people who had fled the war in Ukraine as well as the inhabitants and staff of service homes for the elderly. The instructions for the workshops were simple, at times adjusted depending on the group of people we were working with. First choose a key, we told them. Then imagine you now have the power to unlock one door and lock another. What’s behind your doors? What would you like, first, to free up and release into the world? And, second, what would you like to capture and lock away from the world? Anything, anything that Participants were then asked to choose a coloured paper slip and draw or write down their responses and place their message in a small glass jar. The two objects, the key and the glass jar containing the message, were then attached to the respective ends of a string. This new artistic object was finally hung on wooden tipi structures one by one, creating a swaying assembly of keys and glass-contained messages – an expression of the joined social imagination of the people we encountered at that time, in that place. The installation of eight tipis hung with the messages of around 350 people are currently placed in the garden of the Viktor Runeberg museum in Porvoo.

Now, what about keys. We were interested in how the mundane object of the key, to which everyone has a relation, could be used as a tool to explore deeper social issues on different levels. The idea of working with keys appeared to us very early on, but it was only when we were wrapping up the project that I stumbled upon Key to the City, a participatory public art project conceived by artist and professor Paul Ramírez Jonas. First performed in New York City some twelve years ago, Jonas’ project turned the city’s social and logistical infrastructure inside out, as thousands of master keys were distributed among ordinary citizens, giving them access to more than 20 curious, often privately managed sites across the city – community gardens, cemeteries, bridges and docks, museums, and small businesses. The holder of a master key was free to pass it on to anyone of their choosing in what became a string of key-bestowing ceremonies.

Ramírez’ project explored the city as a composition of spaces that can be locked and unlocked, while exposing the key as an instrument of power pertaining to social contracts, access and belonging. While Ramírez’ keys were shared and passed on, in The Forgotten Keys project, every workshop participant was given the opportunity to choose their own key. The keys we used were partly new, party collected and party donated. When we first started collecting used keys, an Espoo-based locksmith pointed out that metal keys are becoming rarer as our tech-coded society seems to prefer electronically wired, plastic chips. This should not be surprising, as contrary to keys and locks, electronic chips can easily be disabled, re-wired, their locking or unlocking functions can be hooked up to other gadgets and digitally manipulated infrastructures. A step perhaps in a worrisome process whereby our living environments are becoming increasingly privatized and controlled; whereby the net of physical and immaterial borders cast across the globe is rapidly expanding. Access is divided along all possible hierarchy lines – some are granted, many are excluded. In this context, the artefact of the key holds not only a symbolic power, but a politically potent one.

Similarly, the actions of unlocking and locking are complex, politically nuanced. As became clear during our process of distilling the framework of The Forgotten Keys, the action of locking away can be the equivalent both of preserving with the intent of caring, but also of keeping something or someone captive. The action of unlocking can work as release, of setting free, exposing or allowing something or someone to escape. The significance of these actions are fluid as they emerge in relation to the context in which they are performed – what appears as a possibility to some might pose a threat to others.

We saw this ambiguity and complexity of the key reflected in the reaction of many people who participated in our workshops. Many took a long while to grapple with their response, to find something that felt right and a form of expression that felt true to what they felt or wished for. However, in hindsight I feel the response to the question of how to use their keys, jotted down or drawn onto the coloured paper slips, is not in itself a finding that endures the passing of time. The same person might have responded differently upon going to sleep that same evening or waking up the next day. This is why I’m also not particularly interested in sharing here the messages that I witnessed, discussed or helped to write. Some messages were also written in secret. We were not looking to collect any definite statements as if conducting a survey, as much as we were interested in the encounter itself, in creating a framework for people to take a moment of checking in with themselves in the midst of a busy day. Especially in the tense and complex times we are going through, this exercise seemed very important to us. Through inviting people to spend a few moments with us in the workshops, we made a form of proposal: take this time with us, with yourself, and allow your mind to dance a little. And people did, whether with a tinge of initial scepticism or with immediate enthusiasm, people did.

Article written by Emma Hovi

***

EMMA HOVI (1989, Vasa, Finland) is an artist and art educator.

Since 2009 she has lived, studied and worked in different cities internationally: Berlin, Montréal, Vienna and Helsinki where she is currently based. Text, performance, drawing and photography form the core of Hovi’s artistic work. She is interested in questions of social belonging, performativity, everyday choreographies and feminine-coded labour. Often drawing on literary texts or archival material, she works with contradictions, minimal gestures and strange juxtapositions.

Since 2020, she is the co-organizer of Social Choreography Lab Helsinki together with artist and researcher Jon Irigoyen. The Lab is a collaborative artistic experiment at the intersections of movement and political life with the support of Esitystaiteen Seura – Live Art Society at Eskus Performance Center, Suvilahti, Helsinki.

Hovi’s work has been shown in Finland, Switzerland, Austria, Sweden and Hong Kong. Her written work and illustrations have been published in various international outlets. She has also been a board member of the feminist cultural journal Astra and facilitated writing workshops internationally. Currently, she is developing her long-term artistic research project Choregraphy of Chores, while doing pedagogical work for Helsinki’s Annantalo and Espoo’s EMMA Museum.

Contact: @emmakarolinskah